There are many links and similarities between Scotland and Japan, besides my nuptials as a Scot to a Japanese woman, and there were a great many Scots who helped shape modern Japan. Quite often however, these Scots are considerably more well known in Japan than they are back home in Scotland.

I present this series in no particular order, the fact that Jessie Roberta Cowan is not because I deem her to have had the greatest influence on Japan, she is first because currently there is a daily NHK (Japan’s national broadcaster) morning drama about her life, called Ma-san (マッサン), which was Rita’s pet name for her husband. I haven’t had a chance to see the drama yet but my wife apparently cries every time she watches it.

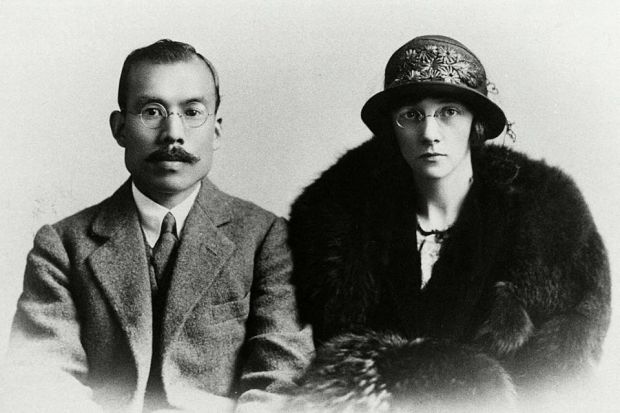

Jessie was more commonly referred to as Rita and her married name is Taketsuru. Rita is referred to as the mother of Japanese whisky being co-founder of the Nikka Whisky distillery along with her husband Masataka who is also known as the father of Japanese whisky. The creation of Nikka was truly a partnership as without Rita’s connections which she had built up teaching English, Masataka would never have found the financing to build his own distillery.

I was going to research and write my own story of Rita’s life as I may well do for future posts in this series, however I found an article on The Japan Times called The Rita Taketsuru Fan Club which I’ve plagiarised parts of instead! The following excerpts are from a story by Jon Mitchell it is a very well written piece and I heartily recommend reading the full article.

Their meeting in Scotland:

“Born in Scotland in 1896, Rita Cowan’s early days had been a model of middle-class gentility consisting of home governesses, piano lessons and a liberal-arts education in English, French and music.

In her 20s, though, two events rent her life asunder — during World War I, her fiance was killed in Damascus, and then, in 1918, her father died of a heart attack.

In the following months, the Cowans’ finances dwindled until, in 1919, they realized they needed to act fast if they wanted to keep the bailiffs from their family home in the town of Kirkintilloch some 12 km northeast of central Glasgow. So it was then they decided to take in a lodger.

The man they chose was 25-year-old Masataka Taketsuru. The Hiroshima native had recently been sent to Scotland by the managers of the drinks company for which he worked. Many decades earlier, Japanese manufacturers had cracked the secrets of European beer and brandy, but one skill still eluded them — the art of making whisky. They’d tried to emulate its taste with spices, herbs and honey, but all to no avail.

Masataka’s mission was to uncover its recipe in the homeland of Scotch whisky itself. At the University of Glasgow, he took courses in organic chemistry, and he also traveled to distilleries all over the country to take apprenticeships in the production of whisky.”

Rita and Masataka were married in Calton Registry Office in 1920 and they moved to to Campbeltown, where Mastaka learned the intricacies of the whisky industry at Hazelburn distillery.

In 1923 they moved to Japan:

“The nation in which the newlyweds found themselves was very different from the one her husband had departed just two years before. The Japanese economy was mired in deep recession and Masataka’s managers were more interested in turning a quick profit with cheaply- flavored spirits than the complex process of making bona fide Scotch whisky.

Disillusioned with their change of heart, Masataka resigned from the company. Rita was unfazed by their sudden financial instability and she supported both of them by pursuing that time-honored profession for foreigners in Japan — teaching English to children and housewives.

While these were undoubtedly difficult times for the Taketsurus, photographs show the pair totally at ease with one another and themselves. Rita clutches a parasol and leans against her husband while Masataka grins confidently at the camera — they appear to be a thoroughly modern couple, thoroughly in love.

By 1923, word had spread of Masataka’s research trip to Scotland and he was hired by Shinjiro Torii (the founder of the Suntory group) to help build a whisky distillery in Yamazaki, Kyoto Prefecture. Rita was happy that her husband would finally have an opportunity to put his hard-earned skills into practice, and for the next six years she taught English while also honing her own Japanese abilities.

Masataka’s time in Kyoto was not as harmonious as his wife’s. He quarreled constantly with Torii over the fineries of whisky production, and these clashes reached a peak in 1929 when Masataka was demoted to the position of manager of a beer factory in Yokohama. He quit — and, once again, found himself out of work.”

On the creation of Nikka after unsuccessful periods working for profit-driven bosses:

Following the disappointment of Yamazaki, it struck Masataka that there was only one way for him to make whisky the way he wanted — he would have to establish his own company.

Without Rita’s connections, he would never have been able to realize this dream. Since 1924, she’d been teaching English to the wife of Shotaro Kaga — the founder of a successful securities company. When Kaga heard of Masataka’s plans, he and two other investors agreed to back the project, and the creation of Masataka’s company, Dai Nihon Kaju (later shortened to “Nikka”).

Upon learning where he was planning to build his distillery, the investors almost changed their minds. But Masataka insisted that there was only one place in Japan with ready access to the barley, peat, coal and water that were vital for Scotch whisky production. That place was Yoichi, a town located in the country’s most inhospitable and underdeveloped island, Hokkaido.”

The distillery turned its first profit in 1940 and Rita continued to play a major part in the success of the distillery until her death in 1961.

The World War II years were difficult for Rita, she was suspected of being a spy by neighbours and their home was subject to raids by Japanese officials. The war years on the other hand were the making of the distillery, there was an embargo placed on imports of Scotch whisky and this brought a wider customer base to the relatively fledgling industry in Japan and Nikka benefited greatly. Nowadays, Nikka whisky is the third most popular whisky brand in Japan.

Legacy:

“Masataka outlived his wife by 18 years, and today the two are interred together on a hillside near the distillery. Walking through the town, I’m delighted to discover that the woman who’d once been ostracized as a potential enemy of the state has since left her indelible mark on the landscape — Yoichi’s main thoroughfare is named “Rita Road” and a kindergarten she helped to establish still bears her name.

After 15 minutes, I arrive at the Taketsurus’ grave. The gray lozenge of stone is lit pink by the setting sun, some fireflies flare brightly and the air smells of freshly-mown grass. In the valley below, I spot the red rooftop of the distillery.

In the years since his death, Masataka’s genius at Scotch whisky production has finally been recognized: In 2007, a bottle of “Taketsuru” was voted the world’s best blended malt; followed in 2008 by 20-year-old “Yoichi” winning the best single malt in the world award.”

Though they never had children of their own, the Takesturu’s adopted Masataka’s nephew Takeshi. In 2002, Takeshi visited Scotland to celebrate the first bottling of the Japanese whisky by the Scotch Malt Whisky Society (of which I am a current member) and whilst he was here he established the Takeshi Tsukuru prize at The University of Glasgow, where his father had previously studied. The prize is awarded to the student showing the best performance in the work placement element of the Chemistry Department’s MSci course.

More info about Rita & Masataka:

- The Rita Taketsuru Fan Club (Full Article)

- Nikka Whisky – Founders

- Kirkintilloch Herald – Raise a toast to Kirkintilloch’s – and Japan’s – first lady of whisky

- The Scotsman – Film tells story of Scot behind Japanese whisky

- The Guardian – American actor Charlotte Kate Fox wins role as ‘mother of Japanese whisky’

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to react!